Permaculture and ideal microclimates are strictly connected. Let’s see how you can use microclimates for permaculture design.

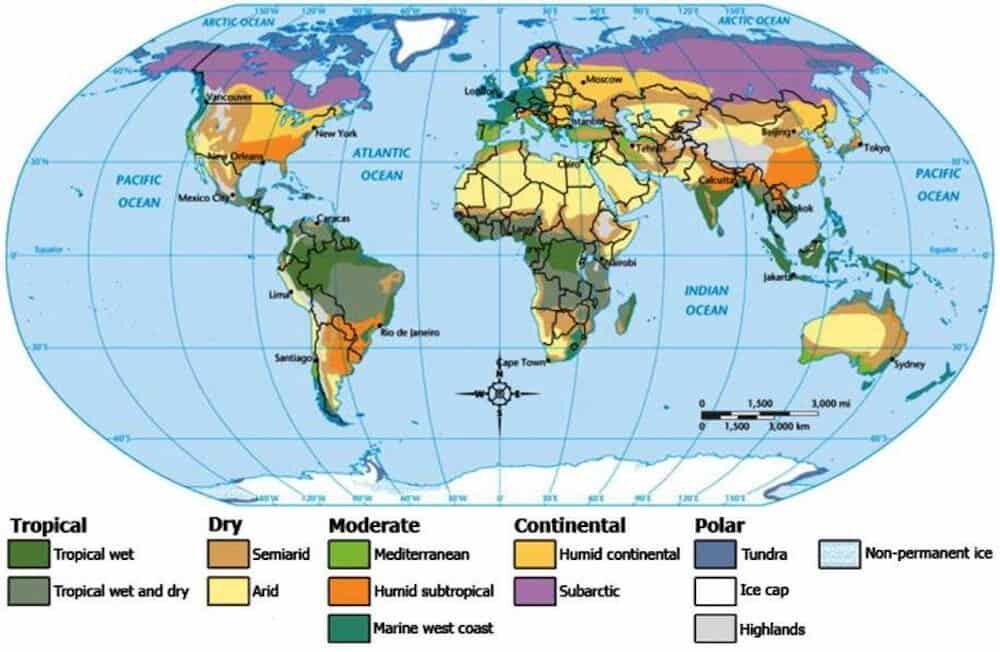

On a scale of permanence, your super-local climate is one of the hardest things to change. Yes, we are facing rapid climate change, on a global and perhaps even galactic level, but those changes took a long time to create, and they would take even longer to undo.

When compared to how easy it is to change a garden bed, or your own mind, climate is much more difficult. Working with nature, rather than against it, means learning the challenges, limitations and advantages of the climate in which you live, and designing your projects accordingly.

Climate is your biggest, most overarching sector, and all other sectors are layers within it. Even social relationships directly relate to the local climate! So, think it over.

Because this mini-course is going out to students all over the world, we won’t get into the specifics of working in any particular climate. It will be up to you to do that research on your own.

In particular, get acquainted with what climate hardiness zone* you’re in, and learn which plants do well in that zone. Start with what grows easily, then, use microclimates for permaculture design for the harder stuff.

*Note: “climate hardiness zones” are not the same as the “zones of human use” as discussed here.

Use Microclimates for Permaculture Design by Taking Advantage of these Factors

This section by Klaudia van Gool

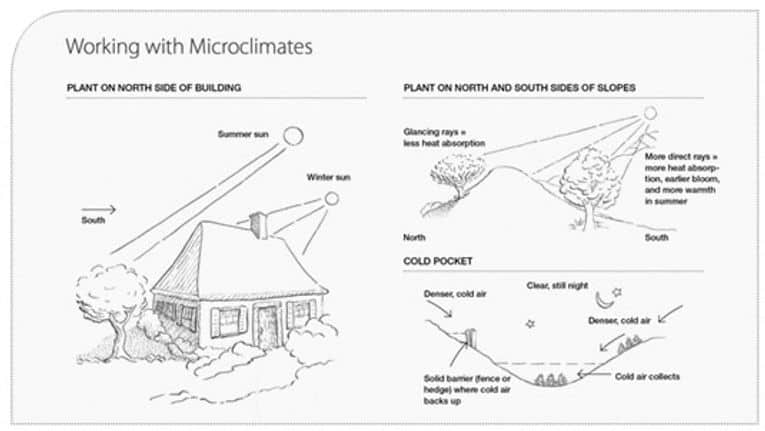

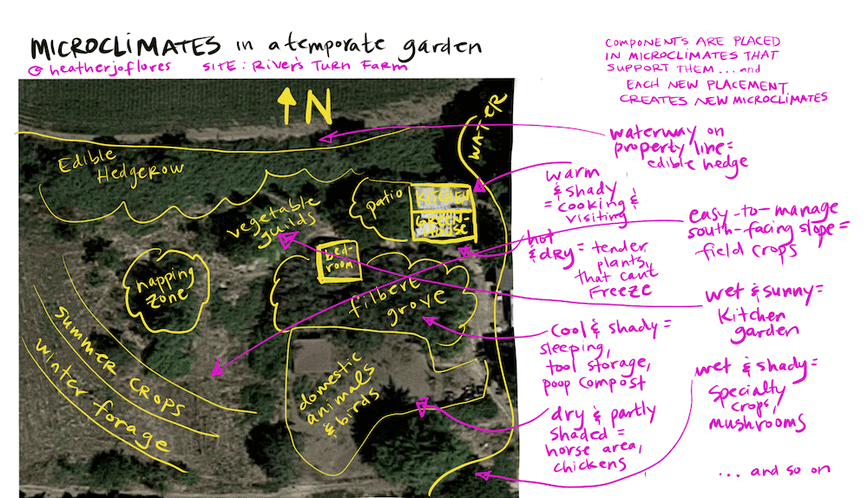

Climate will vary more locally through human structures, topography, altitude, vegetation and water masses. This is called microclimate. By observing and analyzing our microclimate, we can use permaculture design strategies to modify it.

Determining exactly what and where your on-site microclimates exist is one of the most useful applications of a thorough sector analysis. A handful of universal principles can help you find and occupy microclimates for permaculture design within your climate, in which you can grow/do/create things that weren’t otherwise possible.

Creating or maximizing microclimates can help us to harness the beneficial energy within the sectors connected to our designs. In addition, microclimates can also be essential in reducing the impact of the more challenging sectors.

Let’s look at some of these factors in more detail.

- Topography is the shape of the landscape and includes aspect and slope. Hills, mountains and valleys affect how wind moves through a landscape, as the wind moves around hills, speeds up near the top of hills, and funnels through valleys.

- Aspect, the direction land faces, affects the amount of sunlight on a site. For example, a south facing site in the Northern Hemisphere will be a sunny site and can produce more biomass/vegetation.

- Slope, the gradient or steepness in the land, will affect wind speed; this increases towards the top of a slope. Turbulence will be experienced just past the top of a slope. This is important information when situating wind turbines, as they work more efficiently without turbulence.

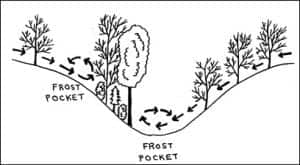

Cold air will sink and move down the slope. Accordingly, the slope will impact thermal zones, and a cold sink may occur just above structures or vegetation lower down the slope or in slightly depressed areas. In colder areas, this can create a frost pocket. - Structures. Urban environments create warmer microclimates through the “heat island effect,” as concrete absorbs more heat than the surrounding countryside. In general, it is warmer in the center of a city.

The hard surface of buildings, roads and straight lines of streets also create a wind tunnel effect, where wind speeds up. Tall buildings can create wind turbulence. Buildings can create a rain shadow, so there is a drier and a wetter side. - Altitude. Temperature decreases with higher altitudes. We also find higher wind speeds and more moisture, because of rain or other precipitation at higher altitudes.

Studying existing vegetation can give us clues to rainfall, wind strength and direction and soil fertility. A way to discover the prevailing wind in our local landscape is by observing trees.

This picture shows how the wind has shaped the trees, restricting growth on the side that the wind blows from, so that there’s more growth on the other side. As well as trees being affected by wind, trees themselves can also affect the wind in the landscape and other microclimate factors.

For example, in temperate climates it is cooler and less windy in a forest while it’s hot outside of it, as trees provide shade and a more moist microclimate and act as a windbreak.

At night, it stays warmer in a forest compared to out in the open, as the trees create shade from the wind and trap warmth. This does depend on the season and vegetation/leaf cover.

On a larger scale, trees contribute to the creation of rain through evapotranspiration.

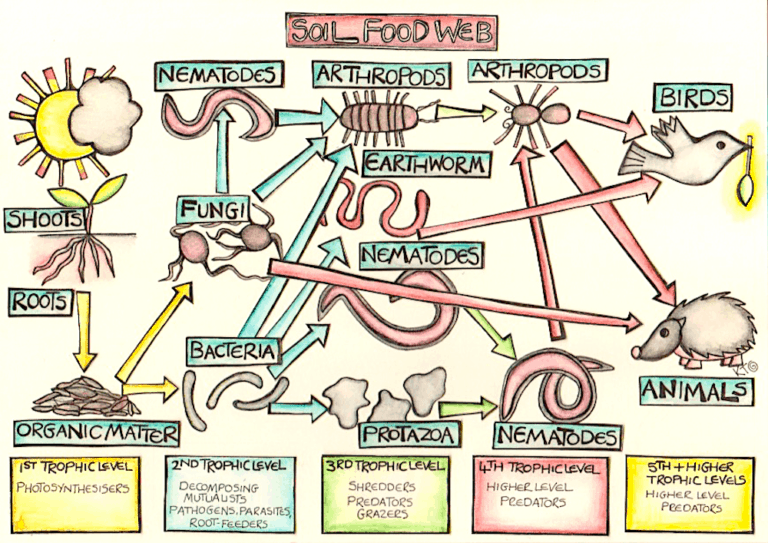

Ecological Niches

Microclimates are directly connected to ecological niches, where organisms occupy a space where they can thrive optimally. Creating, or being aware of having, a variety of microclimates, means you can have a wide variety of niches for more diverse planting, keeping animals, and thus increasing yields.

We can make modifications to a microclimate to reduce and direct wind flow, as wind has a growth limiting effect on vegetation. On a windy site, planting windbreaks and shelterbelts is one of the earliest modifications needed. These create more sheltered areas and can direct the flow of air, including cold air coming downhill.

Using plants to reduce wind is more effective than solid structures, which create more turbulence. In addition, we can choose species for multiple functions, which again creates more yields.

We can modify our local climate or microclimate by adding water storage, which can modify temperature fluctuations. On a larger scale, we can introduce lakes or ponds to modify heat and to add light reflection. On a smaller scale, adding water storage inside a greenhouse or poly tunnel will help buffer extremes of temperature.

In hot climates, planting trees and adding vegetation gives a cooling effect. This is as a result of shade and evaporation, which creates cooling.

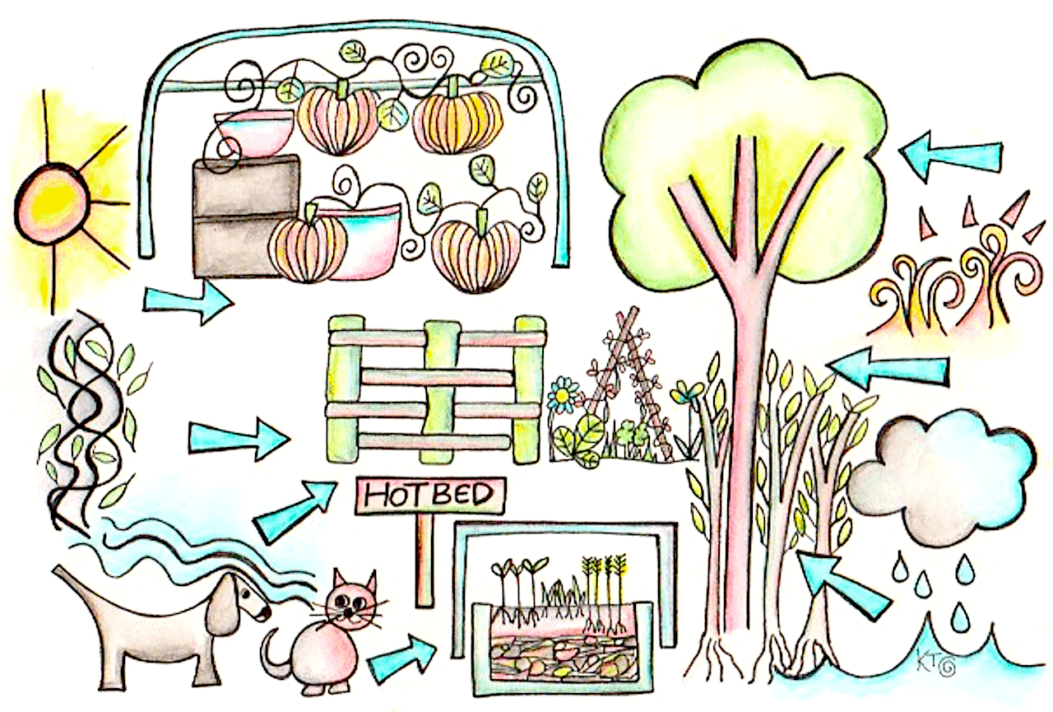

We can modify climate and microclimates for permaculture design through buildings, like adding a greenhouse. When we place a dwelling to the North of a greenhouse (in the Northern Hemisphere) we can make use of surplus heat and protect plants. We can paint walls white in darker, shadier areas to direct in more light and improve growth and ripening by reflecting light. Dark walls reduce frost risk by keeping warmer.

We can use thermal mass like rocks or stone walls to absorb heat and plant more tender plants close up to it. We can also use the cooler temperature of the Earth, whilst it’s warmer at the surface, to create a root cellar for food storage into the Earth, without energy based refrigeration.

In cooler climates, you can create sun traps. These designs are sun-facing and wind-still, creating shelter from cold and destructive winds by capturing maximum sunlight all day. In the Victorian era in the UK, walled gardens were built on large estates to create microclimates for tender crops. Fruit trees were trained up against the walls in fan or espalier shapes.

Hot beds are created by placing small glass frames on top of piles of manure, which generated heat as they rotted down. This is a form of season extension.

How to Make Your Own Microclimates

What can microclimates do for you?

They can help you to:

- Sow seeds early and get plants started while it’s still too cold to grow them outside.

- Grow plants that don’t normally do well in your climate.

- Keep crops going later into the season, often for months after they would have perished in winter freezes.

- Increase your yield, vastly and quickly through these actions.

Hedges and windbreaks

Adding a hedge or windbreak can transform a garden. That’s because they create microclimates for applied permaculture design that are a huge benefit to humans, animals, and plants. While a wall seems to stop a wind completely, there are then eddies and swirls around it, whereas a hedge or windbreak allows a small amount of wind through, enough to stop swirling. However, the wind that passes through a hedge is at a slower, more gentle speed. Wind can cause a lot of damage to plants,plants and not just by breaking them or knocking them over. Wind can dehydrate plants, and salty winds can burn them, leaving the leaves damaged.

Hedges also provide habitat for wildlife, increasing the biodiversity of your plot, which means you will have lots of predators on hand to eat up pests and help keep the ecosystem in balance.

If you are planting a new hedge, or filling in gaps of an old hedge, think about what you want to include in it. What native trees and shrubs would benefit your garden’s wildlife? What plants would mean that, instead of losing part of your plot under the hedge, you are gaining an edible feature?

Multi-row farmstead windbreak in Pocahontas County, Iowa, includes shrubs, conifers, and deciduous trees. Photo by Lynn Betts.

Cloches

A cloche is a mini-glasshouse or polytunnel designed to cover one row or bed, or even a single plant. They give frost protection to the plants they cover, and can save plants when an unexpected late frost is forecast. Using them also means seeds can be sown and plants planted out a bit earlier.

This short video by Tamsin Westhorpe introduces a few different types of cloche.

Cold frames

A cold frame is a small box with a hinged top covered in glass or plastic. They are often built with a used window, with a stick to prop the window open on a warm day.

The sides can be made from bricks, wood or, for a well-insulated cold frame, straw bales. They are like a small greenhouse, just big enough to provide a protected space for small plants in pots so they don’t get too cold in the early and late parts of the season.

Here are some examples:

Greenhouses

A super simple cloche or cold frame can work wonders for extending the season. But truly, if you want to create a beautiful, productive, inspiring, and multifunctional space on your site, you simply must build a greenhouse.

Whether it’s a tiny makeshift hothouse you can barely stand up in, or a hundred yard high tunnel filled with mature trees, a greenhouse will increase the diversity, yield, and enjoyment of just about any site.

Microclimates for permaculture design: Top 10 reasons to build a greenhouse:

- Start seeds early (and late!) Many seeds need warmth to germinate and develop into healthy seedlings. If the growing season is short, getting ahead can make a big difference.

- Protect tender perennials and grow exotic plants. Increase your yields by extending the range of plants you can grow in your climate!

- Protect early blooming fruits (like apricot) from heavy rains. Flowers on fruit trees are often quite delicate and can be damaged by rain, wind or frost, resulting in big losses to your fruit crop for that year. Choose dwarf varieties and plant them right inside the greenhouse.

- Covered space for propagation and transplanting projects. Some plants respond well to a bit of nurturing, resulting in stronger, healthier plants. And gardeners also respond well to a warm place to work on a cold day! Choose a corner of your greenhouse to double as a potting shed, and you’ll spend less time carrying seedling trays around.

- Channel heat into your living space in winter. Build a lean-to greenhouse built against the sunny wall of your house and enjoy the extra warmth in the house.

- Indoor/outdoor space for messy projects. Leave an open area in a section of a larger greenhouse, and you’ll find that you use it all the time, for all sorts of projects.

- Zen gardens! There is nothing like a high-ceiling greenhouse full of blooming, tropical, edible, aromatic, and succulent plants. Build your own mini-arboretum and escape to it when you’re feeling down. A mentor of mine even had a tiny office in his greenhouse, where she would go to get away from the family and write.

- Secure medicinal and high-value plants. A well-built greenhouse with a locking door helps keep both animal and human marauders from making off with your crop.

- Increased humidity for mushrooms, aquaculture. Some greenhouse designs include extra moist, dark, humid zones for cultivating edible mushrooms. Aquacultures also enjoy a more humid environment, and doing something inside a greenhouse could also allow you to add powered pumps, lights, and other features.

- Guest housing! Sleeping in the greenhouse when it’s full of plants is the best!

You can plan space for propagation (seed starting) in a larger greenhouse, or build something intended especially for getting a jump start on the season. For convenience, or for simple ergonomics, this should be a bench or shelf. Extra lighting can be installed and/or heat mats are needed in more Northern climates. In temperate climates, this may not be necessary.

Generally your greenhouse should be attached to your home or nearby, in your zone one area, because you will need (and want) to go there every day.

Larger greenhouses used for preservation crops such as tomatoes, peppers, or fruit trees, should be placed in zone two, unless it is more of a kitchen garden, then it should stay near the house. On a larger scale, it is possible to have all three.

Here’s a beautiful passive solar greenhouse in Alaska.

And another, in Michigan.

Want to learn more about this and other topics related to permaculture, sustainability, and whole-systems design? We offer a range of FREE (donations optional) online courses!

Relevant Links and Resources

What’s the difference between weather and climate?

Tricks for growing tomatoes and other hot-season veggies in a temperate climate (hint: use and create microclimates!).

This quick introduction covers all the bases of microclimate in landscape design.

TreeYo blog offers a solid overview of microclimate opportunities in a permaculture setting.